In honor of the 21st anniversary of the Family and Medical Leave Act, we’ve asked activists around the country to reflect on what FMLA means in their states, how states are taking action to improve upon this seminal law and where we still need to do work. Visit the FMLA 21st Birthday Blog Carnival for blogs from around the country.

By Wendy Chun-Hoon

Imagine being pregnant with twins and your lawful and loving spouse has to sue you to establish joint custody under the law.

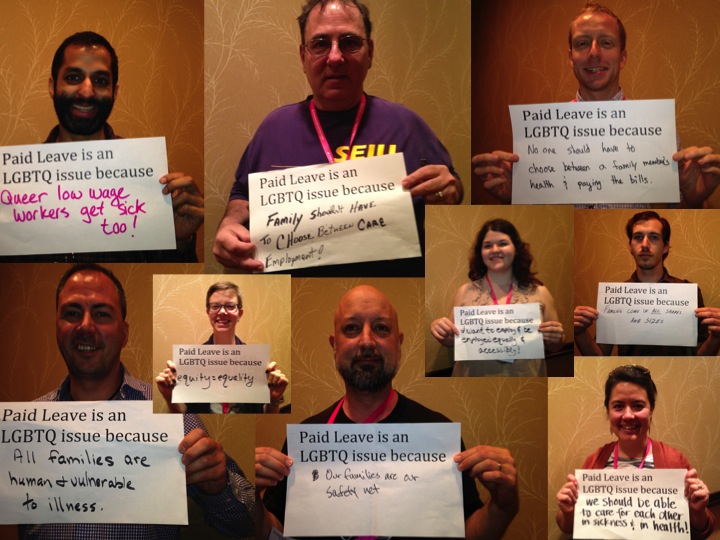

That was just one of the stories I heard last week in Houston, where I traveled along with 4,000 other activists, workers, family members and allies to be at Creating Change – the country’s largest LGBTQ conference. On my first day, I participated in a workshop on families. Most of us were there because we’re starting families and need to learn how to navigate the complex and dynamic web of laws that – for the most part – don’t serve us well. The woman I referenced above had married her wife in Massachusetts. The couple moved their family to North Carolina and were now expecting twins. Under North Carolina law, their marriage didn’t exist. Not only would her wife have to sue her, she also couldn’t use family leave to care for her spouse as she recovered from the birth.

The Family Medical Leave Act, established 21 years ago today, is the only federal policy that protects workers’ jobs when a child is born or adopted or when a loved one falls seriously ill, and it is woefully outdated. Forty percent of the workforce doesn’t qualify. Many who do can’t afford to sacrifice their paychecks for an unpaid leave. The FMLA provides too few protections for workers and their families – and even fewer for LGBTQ families.

In far too many workplaces in across our country, LGBTQ workers are fired because their employers are legally allowed to discriminate against them for their sexual or gender identity. In far too many communities, LGBTQ couples’ relationships aren’t recognized and LGBTQ parents aren’t able to establish a legal relationship to their children. And in far too many households, LGBTQ partners aren’t able to care for each other without risking wages or, worse, their jobs because under the FMLA’s restrictive definition of the word “spouse,” their relationship doesn’t count.

My role in the workshop was to educate folks about their rights under the FMLA. There was some good news. In 2010, the Department of Labor issued a ruling affirming that the “in loco parentis” (standing in the shoes of a parent) provision of the FMLA applies to same-sex couples. For LGTBQ families (and many other families) this is critical. It helps to formally establish a parent-child relationship for non-birth parents who are very much, in fact, raising their kids. The North Carolina partner who wasn’t carrying the twins could take leave to care for them – just not for her wife.

I was able to name one other highpoint in my presentation. When, in June of last year, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Edith Windsor, overturning key parts of the Defense of Marriage Act, suddenly certain married LGBTQ couples were granted FMLA coverage to care for each other in emergencies. Married couples who live in a state with marriage equality can qualify for FMLA leave for their partner. However, it was extremely hard to tell that woman her spouse would not be able to take FMLA leave to care for her after the birth or should she fall seriously ill.

Only 25% of kids today are being raised in this country’s “traditional” concept of the mom-dad, two-parent household. It’s long past time to reform the FMLA. We can start by treating same-sex married couples the same as we treat different-sex married couples by not conditioning FMLA coverage on where you live. This is something the Department of Labor could issue a ruling on now.

But we also need to change the FMLA to establish a more comprehensive definition of family. This is especially important, for example, for older LGBTQ couples who aren’t married as well as for those who have no interest in marrying. We all benefit when laws recognize and strengthen the many forms of family in the U.S. today.