The Power of Voting Can Change Generations

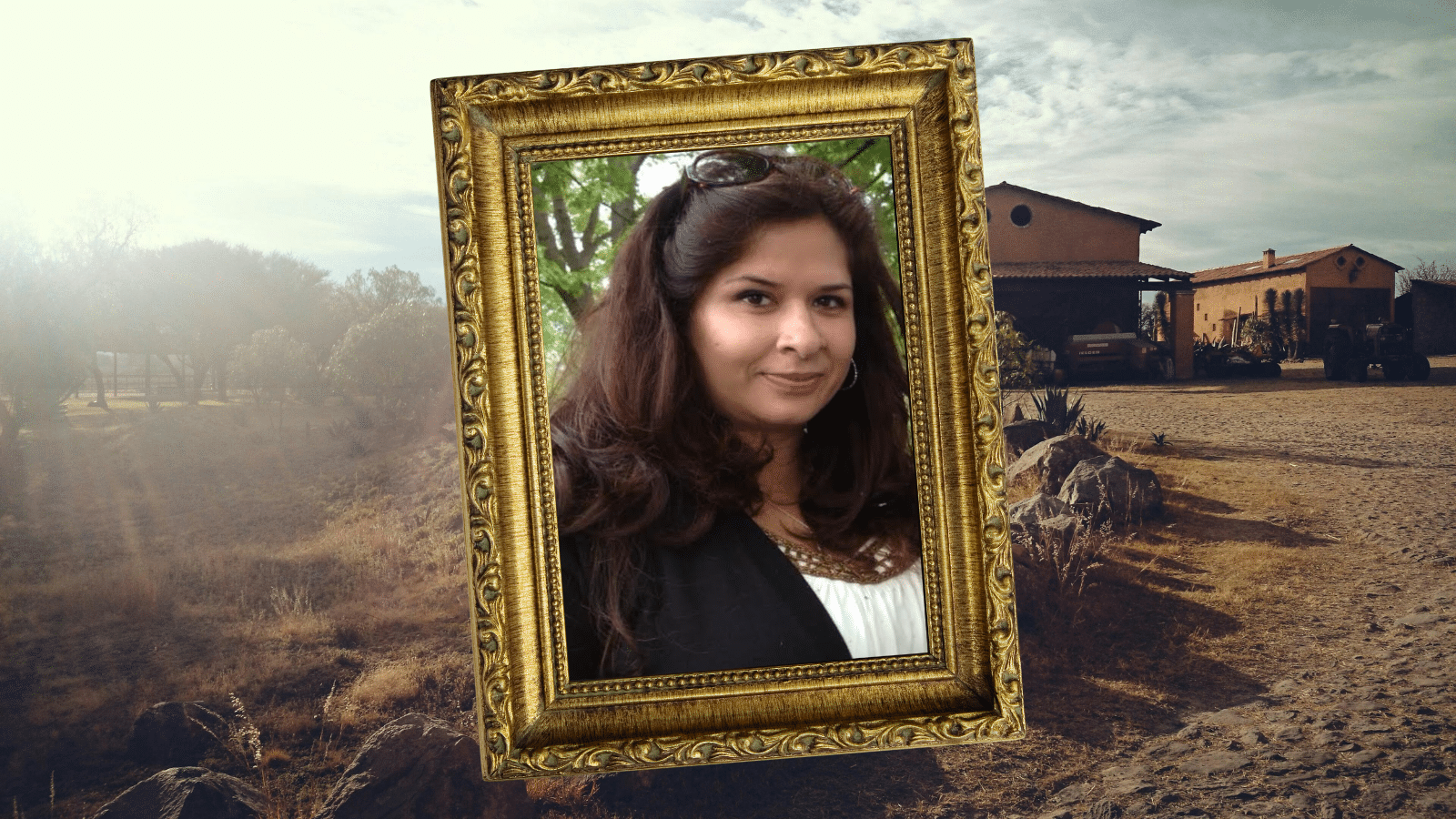

by Linda Garcia Barnard (she/her)

Hispanic Heritage Month has come and gone. The stark contrast between the many commercials and posts celebrating Hispanic cultures alongside the constant political condemnation of immigrants in the media was senseless. It took me back to my 8-year-old self, a girl filled with bewilderment as to why my father, with his dark brown skin and heavy accent, acted more like a white man.

You see, my father was an undocumented field worker in the ‘50s. I recently learned he was deported twice during those years. It wasn’t until he attained his citizenship in the late ‘50s that he became a proud American who seemed to forget his roots and his struggle. I wonder if he thought his papers gave him power that made him better than others who looked like him, others that were still in the struggle to find a pathway to citizenship. I was too young to understand the impact of oppression then, but am seeing a similar pattern in multi-generation immigrant family members today who repeat sound bites about immigrants coming here for a better life as ‘thugs bringing drugs and taking our jobs‘. They forget the only reason they are here is because someone in their family made that same crossing to give future generations a better life. Is that how some view their ancestors? It seems so senseless.

I believe my father tried to forget where he came from so that he was fully accepted as an American. Although English was his second language, he condemned the use of slang and would scold us to speak “proper English”. He refused to teach us Spanish but I remember bits and pieces of when he sang beautiful old Spanish ballads and played guitar, or when he ordered from the deli at El Rey grocery. He refused to talk about his life as a youth but told us he met his first wife in Mexico while she was vacationing, they fell in love and then he came to the United States with her. The most he shared about back home was that my Grandma’s name was Severita; Grandpa was Everisto; and we had an Uncle Juan and Aunt Carmen. My father’s birth name was Felipe but he legally changed it to a more Anglo-sounding name, Philip, which now makes sense.

The atrocities that made him flee Mexico and trek all the way to Wisconsin multiple times, I’ll never know. What I do know is that he prided himself on hard work — whether in the yard or as a mechanic for the City of Milwaukee — he gave it his all and valued every dollar he made. His work ethic passed on to his children and grandchildren who serve in the community, military and as first responders. We inherited a sense of duty to give back for the opportunities we have been given. But even in our own family, we have fallen to the intentional divide and conquer strategy of us vs. them. We can no longer talk about politics at the kitchen table without inflicting emotional harm on one another. It’s a sad reflection of many families with immigrant roots today.

The struggle for my father was real, and I vividly remember how proud he was of his duty and power of his right to vote. At election time, he would tell us it was a privilege to have the ability to vote and that sometimes voting is the only way to be heard. He was well known to reach out to the alderperson in our community whenever he had an issue to resolve. I guess because he likely never missed voting in an election, he had the courage to speak up when something wasn’t right in the neighborhood. Not that one needs to vote to have access to an elected official or to services, but it does make sense that those who vote have a stronger voice.

If my father was alive today, he would soon be celebrating his 100th birthday. In his last lucid stages of dementia, he would talk about how he missed his horses and the butcher shop in the old country. When I would ask him to tell me about how and why he crossed the border, he would reply, “I do not know what you speak of.” and he would only repeat his story that he met his first wife there and moved to America with her. He refused to remember his life as an undocumented person and tried to forget his struggle even in his dying days. That was shameful of him and scarring for me because there’s an entire line of ancestry rich with culture and stories that I’ll never know. I only sense their strength and protection when I need them most.

Therefore, it is in honor and celebration of my ancestors and my father’s journey for a better life in the United States that I will use my power to vote. As a second generation Mexican-American, I learned as a little girl that it’s not okay to forget our roots, forget our struggle or forget our people. We must continue to create a path for others to build their lives too, not tear them down. We can do this by casting our votes for the values that made the U.S. a beacon of hope for all immigrants whether they crossed the border by river or by ocean. My hope is that other generations of immigrant families do the same because it is the only way to continue to build our legacies.

Let’s use our power and vote our family values. It just makes sense.